From TALIA BAIOCCHI, Special to THE SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

Mantineia, the Peloponnese, Greece — Sunday, June 26, 2011

Mantineia, the Peloponnese, Greece — Sunday, June 26, 2011

This should be the time to be a Greek winemaker. The country is amid a quality revival of world-class wine regions from the islands to Greece’s northern border.

But no matter the centuries since Sophocles ruled the stage, the Greeks still remain disposed to a good old ancient bout of reversed fortunes. The trouble this time? The economy.

Wine sales within the country are down more than 40 percent over the past 12 months, threatening a newly revived industry that, until recently, sold 90 percent of its production at home.

Yet this pinch might provide a push for Greece to make a lasting impression elsewhere in the world. Potential tragedy may well be averted. « Before, Greek winemakers wanted to see wines exported, but there wasn’t enough of a reason to put that much effort in, » says Markus Stolz, an export agent in Greece who is working with several U.S. importers, including Oakland’s WineWise. Now there’s certainly a reason.

Greek producers looking to pivot on the economic decline have adopted a new focus on exports. At the same time, high-profile American importers have taken a new interest in Greek wines.

According to the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in 2010 the value of Greek wine exports to the United States went up more than 12 percent over 2009. While that may be not enough to balance the 40 percent drop at home just yet, it suggests that Greece’s unfortunate circumstances may offer the best chance it’s ever had of capturing the U.S. market.

Did not know the market

« For many years Greeks were not truly exporting, it was just Greeks transporting the wines to the Greek communities abroad, » says Yiannis Paraskevopoulos, winemaker for Gaia Wines and a mentor to many of Greece’s up-and-coming winemakers. « They didn’t expose the wines to the Americans; they were very self-restricting in a way, and they did not know what the market was after. »

And the wines weren’t being treated like serious fare, insists Ted Diamantis, owner of Diamond Wine Importers, one of the country’s top Greek portfolios. Importers, he says, « didn’t care about what they were selling or how it was stored. They were just dumping it off to their buddies at the Greek restaurants. »

That’s changed. Diamantis’ Greek wines are now distributed by Michael Skurnik Wines, one of the most respected U.S. importer/distributors. This is a huge psychological leap for Greek wines in the United States, and it demonstrates well the trend of larger, non-ethnic distributors and importers seeing a gap in their portfolios they hadn’t noticed before.

Importers’ portfolios

« I’ve had numerous job offers from importers looking to build Greek portfolios, » says Kamal Kouiri, wine director at Molyvos in New York, home to the country’s largest Greek wine collection. « You see a lot of that right now. »

In some ways, Greece’s breakneck rise to legitimacy in the U.S. market mirrors that of southern Italy. By lowering yields, rediscovering their ancient roots, and paying careful attention to growing areas, the Italians were able to buck their bad reputation as bulk producers and educate the world on the wonders of everything from Aglianico to the wines of Etna.

With hundreds of indigenous varieties, a wine history that dates back more than 8,000 years, and no shortage of unique terroirs, Greece faces a similar opportunity.

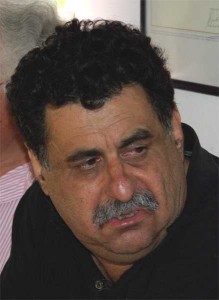

Left: Yiannis Tselepos, Managing Director of Ktima Tselepos in Arcadia in the Peloponnese, a leading figure of the Greek wine industry.

Left: Yiannis Tselepos, Managing Director of Ktima Tselepos in Arcadia in the Peloponnese, a leading figure of the Greek wine industry.

On the Peloponnesian peninsula there is Nemea, the spiritual home of Agiorgitiko, which drinks like a love child of Sangiovese and Merlot, with its own unique brand of brooding rusticity.

Just southwest of Nemea, on a plateau about 3,000 feet above sea level, lies the region of Mantineia, home of Moschofilero — a gray-skinned grape that produces floral, nervy white wines that are among Greece’s finest.

Consider Santorini now, one of the few volcanic islands in the Aegean Sea and perhaps Greece’s most well-known growing region. The island’s famous basket-trained Assyrtiko vines are some of the oldest in the world (many root systems date back more than 400 years), and the almost total lack of rainfall (grapes must rely on the morning mist off the ocean for hydration) makes it one of the most extreme places to grow wine. The resulting whites are high in acid and intensely mineral-driven, with the potential to age like German Riesling.

North, in Naoussa and Amyndeon, the Xinomavro grape is increasingly touted as « the Nebbiolo of Greece » for its aromas and formidable tannins. It may not become a rival for Barolo, but it has rapidly defined itself as the country’s standout red grape.

The point is that Greece could easily compete with its more famous neighbors.

Marketing for Greek wines abroad has been notoriously disorganized. But while there’s a burgeoning interest from U.S. importers and distributors, there are still some issues. Two U.S. trade efforts have both been small and narrowly focused, and so the one crucial thing Greek winemakers need to do — educate their potential customers about the country — largely hasn’t happened. Without a guide, Greek wine is still, well, Greek to consumers.

Cannot use Italy’s model

All of which leaves Paraskevopoulos trying to figure out how to tackle the market. « We’re a tiny country; we produce 15 times less than Italy, which means we cannot adopt their model, » he says. « They also have, for one, many Italian restaurants that act as vehicles for the wines abroad. Greeks do not have that. » Plus, with a restriction on new vineyard plantings under European Union law, Greece’s production isn’t getting any bigger. As much as the country might seek to parallel southern Italy, Greece must carve a different path.

Now is the time. With the growing U.S. interest in Greek wine, a consistent rise in quality, and a new eagerness by Greek winemakers to look abroad, Greece — in spite of its economic hardships — is in a prime position to make its case.

Talia Baiocchi is a freelance writer in New York and wine columnist for Eater.com.

A taste of Greece

Above: the splendid Mercouri vineyard surrounded by palm trees. Below Right: Vasilis Kanellakopoulos, Mercouri Managing Director.

— 2006 Mercouri Estate Vin de Pays des Letrinon ($28, 13% alcohol): located on the western side of the Peloponnese at Korakochori on the Ichtis cape, Domaine Mercouri is one of Greece’s oldest estates.

— 2006 Mercouri Estate Vin de Pays des Letrinon ($28, 13% alcohol): located on the western side of the Peloponnese at Korakochori on the Ichtis cape, Domaine Mercouri is one of Greece’s oldest estates.

The Refosco, which makes up 85% percent of this blend, was originally brought to the estate from northern Italy in 1870.

The remainder goes to Mavrodaphne, an indigenous red grape more often vinified sweet. Dense, brooding fruit; tobacco leaf; flowers; vibrant acidity; and fine tannins.

Importer (in the United States): Athénée Imports.

— 2006 Gaia Estate Nemea Agiorgitiko ($35, 14%): a polished, skillful take on Agiorgitiko. Bright Sangiovese-esque black cherry and plum framed by dust, pepper and anise. Nicely structured, with tannins that suggest longevity and acid that practically rings the dinner bell. Importer: Athénée Imports.

— 2010 Skouras Peloponnese Moschofilero ($15, 12%): George Skouras is one of the pioneers of modern Greek winemaking, and his wines are still among the best representations of variety and place. A classic Moschofilero nose of rose water, pear and minerals with a touch of white pepper. Racy on the palate. Importer: Diamond Importers.

— 2010 Sigalas Santorini Assyrtiko ($22, 13.5%): although white Assyrtiko%3

TO TED LELEKAS, Mmmm… ton vin! GREEK CONTRIBUTOR

Dear Ted, I forwarded to our blog this article from The Chronicle because it does echoe your optimistic post on October 4, 2010, as the present situation in Greece is quite dramatic, if not tragic. « Potential tragedy may well be averted » says Talia Baiocchi the writer.

I sincerely hope that Greek wine exports will do well in the United States.