By JOSHUA MALIN / VINE PAIR — October 16, 2014

Winehaven: How The Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 Gave Birth To The World’s Largest Winery

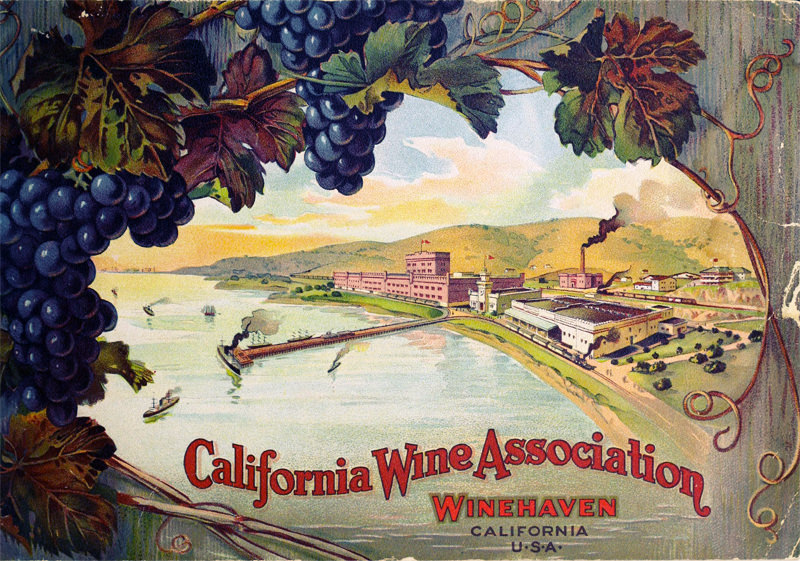

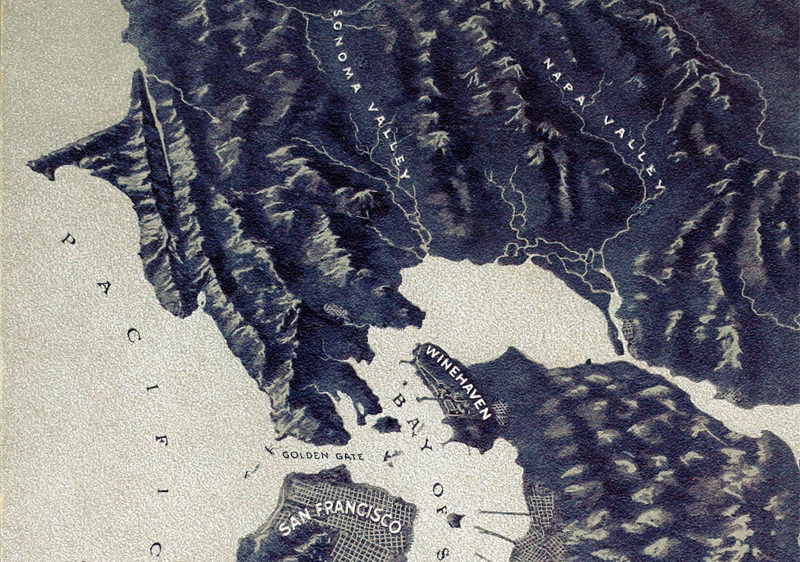

In the years leading up to Prohibition, the largest winery in the world sprawled across a 47-acre campus, perched upon the San Francisco Bay. Its name was Winehaven. At its peak capacity the winery and its warehouses could hold 12 million gallons of wine, which were distributed by sea from an 1,800 foot wharf, and by rail via privately owned, electrified train tracks.

Winehaven was the crowning, physical accomplishment of the California Wine Association (CWA), a firm that was founded in 1894 to monopolize the California wine industry. In building Winehaven the company achieved its most audacious goals, defining the contours of the way California wine was marketed for decades to come, long after Prohibition stamped the company out of existence.

In 1894, seven of California’s largest wine merchants banded together to form the California Wine Association. The CWA quickly established their near-monopoly in wine production and distribution in the state, fending off challengers and absorbing competitors as they consolidated their position into the turn of the century. Exact figures are disputed, but it’s probable that the CWA was responsible for upwards of 85% of California’s wine production at its peak. Thomas Pinney’s A History Of Wine in America states that “by 1902 the CWA controlled the output of over fifty wineries, producing some thirty million of the state’s forty-four million gallons of wine.”

The merchants who banded together to form the CWA had struggled through more than a decade of difficult years. Poor marketing and unclear labeling drove down prices on quality grapes as bulk buyers blended the good and the bad into generic wines. This created a vicious cycle where falling prices encouraged questionable viticultural practices in an effort to increase yields. These practices produced their intended result: soaring production, which depressed prices even further. As France’s vineyards rebounded from the scourge of phylloxera, hopes of California wines supplanting French imports on the East Coast and around the world as the world’s ‘export wine’ of choice were dashed.

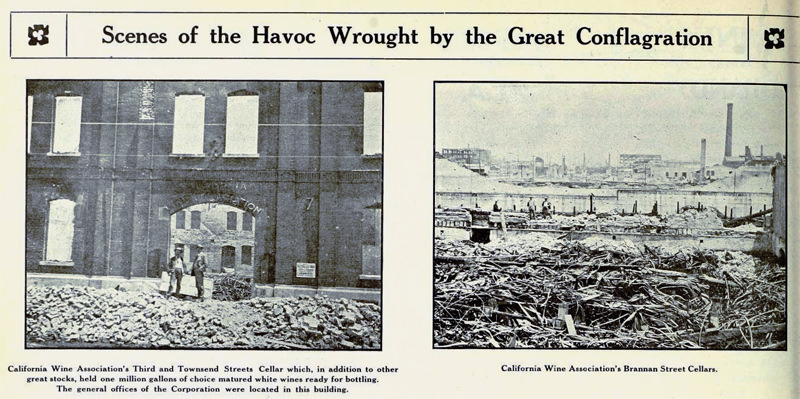

The CWA’s founding partners came together to break this vicious cycle. Their pioneering marketing and modernization efforts, along with a healthy dash of standard late nineteenth century monopolistic tactics reversed the tide. The Great San Francisco Earthquake struck twelve years later, in 1906. The earthquake and the subsequent fires left the vast majority of the city in ruins, including the CWA’s South of Market headquarters and winery. Winehaven would emerge from its ashes.

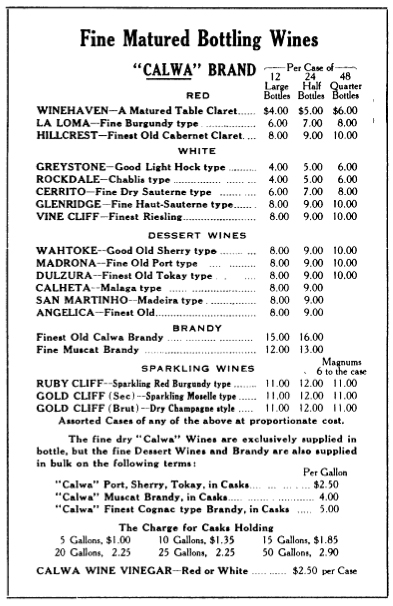

While the CWA was unquestionably cutthroat in their business dealings, their efforts to raise the price of California’s wines were not simply the product of consolidation. The CWA blended grapes from their large vineyard holdings around the state to company standards at their headquarters, and even aged them for a time, before they were distributed for sale under various labels of the Calwa brand.

The California Wine Association’s universal logo adorned all Calwa wines, a mark of the company’s quality:

When the earthquake struck, multiple sources confirm that millions of gallons of wine were lost. The ‘Calamity Edition’ of the Pacific Wine & Sprits Review, a combined April and May edition of the trade journal, estimated the CWA’s losses in a section titled ‘Wine That Went Up In Smoke’: In order that the trade may have some idea of the enormous quantities of wine that were destroyed by the fire, it is only necessary to mention a few of the leading houses whose plants were burned. For instance, the California Wine Association in its San Francisco cellars lost 4,750,000 gallons of wine.

In that same edition, another report ran on the value of CWA’s concrete cellars, which were responsible for saving an equally massive quantity of wine: The California Wine Association saved from its cellars on Third and Bryant Street, 2,100,000 gallons of wine which was found fit for distilling purposes, and will make brandy. The salvage of this wine is proof of the wisdom of the Association in making all their cellars concrete, both sides and bottom.

That edition also carried a fantastical bit of marketing in its report, hyping to the heavens what must have been absolutely dreadful wine (emphasis added):

The Association also saved 35,000 bottles of wine which had gone through the fire. This was all that was saved out of a stock of 250,000 bottles. These wines by reason of tremendous superheating and slow cooling have developed marvelous qualities. In richness of bouquet and body and color, they are probably the finest wines that have ever been produced in California. Of course, this is a very expensive way to produce fine wines, and the Association will certainly not endeavor to repeat their success in this way. However, the wines will be cased and specially labeled and sold throughout the United States as souvenirs of the great conflagration.

By this time the CWA was well established, with California’s turn-of-the-century bankers taking a leading role in the company. While other wine producers ran reassuring notices that they had either escaped the earthquake’s damage or were prepared to recover, the CWA submitted this ad for a few months, simply letting their capital position speak for itself:

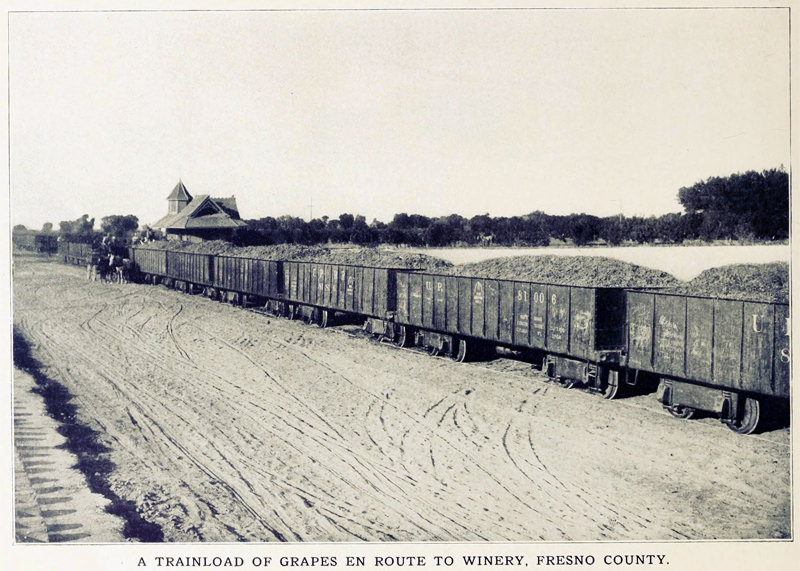

In the September 30th issue of the journal, the The California Wine Association’s recovery plan was finally revealed. It would be a month later before the name Winehaven was publicly settled upon, but the audacity of the forty-seven acre project on Molate Point was laid out: … The next important structure will be the winery, which will have an area of 600 x 150 feet, in which the enormous quantity of grapes heretofore mentioned will be converted into wine. There will also be a sherry house 80 x 100 feet and an office building and laboratory 80 x 100 feet. The Association will also install a plant in which they will manufacture all their own cooperage. They will also manufacture their own boxes for wines in glass. This plant will be of such magnitude as to handle ten million gallons of wine and it is not only so situated as to be free from danger of fire, but also has ample space to grow.

The magnitude of the plant will be better appreciated when it is stated that upon its completion it will be equipped not only for storage, but the making of wine, and will have a crush capacity of 25,000 tons annually. The plan will include a grand main building which will be 800 feet long and 185 feet deep with a basement and two stories.

The only thing crazier than the audacity of the plan was the fact that it did not merely come to fruition, but that Winehaven grew to a capacity of 12 million gallons by 1910, less than four years after ground had been broken.

When Winehaven was in full swing it was a true company town, with housing for hundreds of employees. Less than ten years later, Prohibition put it all to an end. The company’s assets were sold off and the era of near-monopoly in California wine came to an abrupt end. The Navy eventually bought the property to use as a fueling station during World War II. They held onto it for decades until the site was finally decommissioned in 1995. The original “grand main building” remains, crumbling, awaiting its next chapter.