By JASON WILSON | The New York Times | May 26, 2018

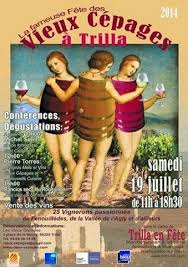

In recent years, you may have noticed some unfamiliar names on wine lists alongside your usual chardonnays and pinot noirs — strange, hard-to-pronounce grapes from places where, until recently, many people didn’t even realize wine was made.

The trend has been around long enough that some of the names, like albariño from Spain or grüner veltliner from Austria, are considered old hat by serious wine enthusiasts. Nowadays, the trendy names include juhfark, from Hungary; obaideh, from Lebanon; chasselas, from Switzerland; and saperavi, from the republic of Georgia.

Some of this newfound love for obscure grapes can be overbearing, a way for wine geeks to draw a line between those who drink pinot grigio — “book club wine,” I’ve heard it called — and the true connoisseur. Still, whether they mean to or not, the snobs may be onto something. In seeking out the rare and arcane, wine geekery may actually be leading us toward richer biodiversity and sustainability, and perhaps even a more enjoyable drinking experience.

Credit Alicia Adamerovich

For years, the global wine industry had been devolving toward a monoculture, with local grape varieties ripped out in favor of more immediately profitable, mass-market types. There are 1,368 known wine grape varieties, but nearly 80% of the world’s wine is made from just 20 kinds of grapes. Many of the rest face extinction.

Yet in small geographic pockets, winegrowers have stuck with their native varieties. It’s probably not a surprise that the kind of winemakers who grow obscure grapes are often the same ones who are committed to organic farming, hand harvesting and natural winemaking techniques.

I spent some time recently in the Swiss Alps with a man named José Vouillamoz, a world-renowned geneticist and botanist. He’s also a co-author of the encyclopedic tome Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavors. Needless to say, he knows a lot about a lot of grape varieties, but that day we were talking about Swiss wine.

Switzerland is hardly a wine powerhouse, and only 2% of its wines are exported. Mr. Vouillamoz poured me what he called “one of the rarest wines in the world,” made from a grape called himbertscha, which he’d helped rescue from a forgotten vineyard high in the Alps. Its two acres represent all that’s left of himbertscha vines, from which less than 800 bottles are made each year.

Himbertscha is one of the strangest white wines I have ever tasted — like a forest floor that’s been spritzed with lemon and Nutella. “Critics claim that obscure varieties like this will never be as good as Bordeaux or Burgundy,” Mr. Vouillamoz said. But tastes change. “What about in 50 years? One hundred years?”

My question was different: Why had grapes like himbertscha nearly disappeared in the first place?

“People became ashamed of the old-time grapes, the grapes of grandpa,” Mr. Vouillamoz said. “They began planting the so-called noble grapes, and they would disregard the rest,” — “Noble” is the historic designation for grapes like chardonnay, sauvignon blanc and pinot noir that made Bordeaux and Burgundy famous and are now grown everywhere from California to Australia to South Africa to China.

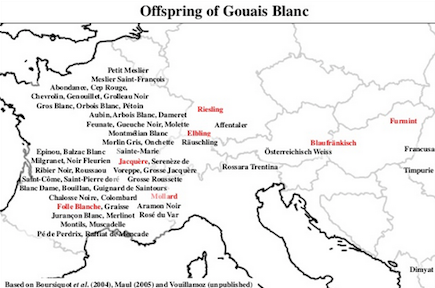

Wine has long been tied to power and money. Mr. Vouillamoz poured a wine made from gouais blanc, a white grape that had been banned across Europe, by various royal decrees, since the Middle Ages. Monarchs considered it a peasant grape that made bad wine — “gou” in medieval French was a term of derision. Through DNA testing, though, gouais blanc was found to be the “mother” of around 80 modern varieties, including chardonnay (above).

Throughout the centuries, one monarchy after another decided which noble grapes were to be grown, and then they outlawed others. In the Holy Roman Empire, Frankish wines were favored over ones that were Heunisch (“from the Huns”), a pejorative describing anything from the eastern Slavic lands.

In 1395, the Duke of Burgundy banned gamay (“a very bad and disloyal variety”) and insisted that only pinot noir be planted. For hundreds of years, the wines of the Habsburg Empire were counted among the world’s most important; once the empire fell, many of its wines were forgotten for almost a century.

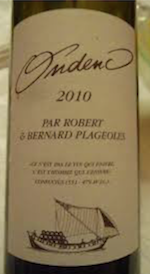

Wine has always been intertwined with such geopolitics. Why, for example, don’t more people know about the delicious and good-value wines of southwest France, made from such grapes as braucol from Gaillac, tannat from Madiran, or négrette from Fronton?

Well, back in the 13th and 14th centuries, the merchants of Bordeaux began to see the wines of southwest France as a threat to their economic interests. So Bordeaux, wanting to keep its dominance over the wine trade with England, decreed that no wine could be traded out of Bordeaux until the majority of Bordelais wine had already been sold. This dealt a crushing blow to the winemakers in southwest France, while keeping the Bordeaux wines, made from noble grapes like cabernet sauvignon, merlot and sauvignon blanc, on top.

When the winemakers in southwest France could no longer sell wine at premium prices, those areas settled into a provincial backwater. Some of the growers ripped out their vineyards and replanted with noble grapes. Others continued to work with local grapes and made low-cost, everyday “peasant” wine. The rest of the world mostly forgot about braucol and négrette and tannat. Because of Bordeaux’s power and influence, it’s taken more than 500 years for us wine geeks to rediscover the indigenous wines of southwest France.

Not everyone in the wine world thinks this revival of obscure grapes is a great thing. A few years ago, the influential wine critic Robert Parker, who has made a career promoting noble grape varietals, scolded those of us who enthusiastically embrace such “godforsaken grapes” as “Euro-elitists.” This was power speaking, the influential gatekeeper positioned just like the monarchs of old.

But Mr. Parker is on the wrong side of history. Those blaufränkisches and rkatsitelis on your wine list aren’t going away. Every new grape you’ve never tasted before offers the chance to experience a new flavor — not to mention the environmental benefits of a more diverse and sustainable industry. In this increasingly globalized, homogenized world, that’s not just a matter of snobbery.

Mr. Wilson writes about wine and spirits.

Read also In the beginning was the grape by Jancis Robinson.

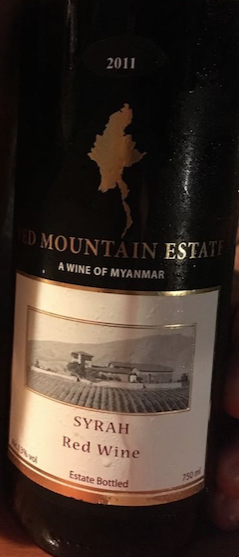

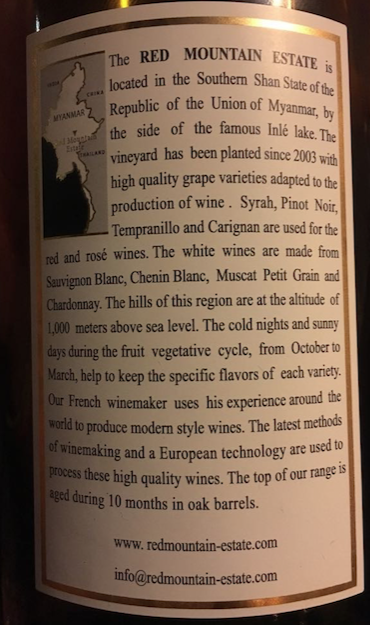

Addendum. While Western drinkers may look for new old varieties as observed by Messrs. Wilson and Vouillamoz and by Mrs. Robinson, Asian countries as below in Myanmar (Burma) rely on old new French varieties and winemakers.