Ernst Jünger : « Dans la Légion, j’avais le n°15314. Mes parents m’envoyaient de l’argent car ma solde n’était que de 4 pfennings, soit 1 sou. Un litre de vin rouge, de ce lourd vin rouge d’Algérie, coûtait seulement 1 sou. Alors, j’ai appris à boire du vin rouge, et je m’y suis accoutumé, jusqu’à aujourd’hui. Cela veut dire que ce ne peut pas être très dangereux le vin rouge. » (Interview radio)

L’époque dont parle Ernst Jünger est celle de la 1ère guerre mondiale. Il est mort à 103 ans, en 1998.

Voir plus bas l’article du New York Times WINE AND WAR.

« Un jeu magnifique et sanglant auquel les dieux prenaient plaisir » : on songe à Homère et à la guerre de Troie et c’est 1914-18 vu par Jünger. L’idée que des hommes aient pu consentir librement à une telle épreuve est presque scandaleuse aujourd’hui. On préfère penser que les combattants furent des victimes et souligner ce que leur héroïsme doit à la contrainte. Alors évidemment, Jünger dérange. En 1920, Orages d’acier décrit une expérience des limites dont il a clairement consenti à payer le prix. Un jeu de vie ou de mort, comme une partie de chasse, mais dotée d’une justification morale : chasseur et gibier échangent constamment leur rôle. Jünger, qui n’est pas un fou, ne nie pas que la guerre soit terrible. Simplement, il montre qu’elle transforme l’homme de l’intérieur autant qu’elle l’agresse de l’extérieur. Sous le feu, il prenait des notes. Entre ces notes et les livres, « il y a toute la distance qui sépare l’action de la littérature ». Littérature : il s’agit de cela, plus que d’histoire. C’est l’essence anhistorique de la guerre éternelle que Jünger découvre sur le front et consigne dans son journal. En joignant aux versions définitives un choix de textes et de fragments retranchés, ce volume prend en compte les journaux de Jünger dans toute leur complexité. |

|||||||||

Édition de Julien Hervier avec la collaboration de Pascal Mercier, François Poncet – TOME II : 1939-1948 : Avant-propos de « Rayonnements » – Jardins et routes – Premier journal parisien – Notes du Caucase – Second journal parisien – Feuillets de Kirchhorst – La Cabane dans la vigne, trad. de l’allemand par Maurice Betz, Henri Plard et Frédéric de Towarnicki. 1939. Mobilisé par un régime qu’il déteste, Jünger est à nouveau sous l’uniforme. Ce n’est plus le même homme, ni la même armée. L’expérience, elle aussi, sera différente. Après une campagne au cours de laquelle il n’est jamais en première ligne, et à part une mission dans le Caucase comme observateur, il est un occupant à Paris, puis le chroniqueur d’un coin d’Allemagne occupée. Les journaux de la 1ère guerre s’organisaient en grands chapitres; ceux de la 2nde sont datés au jour le jour. Dans un décousu apparent et très concerté, ils font place à des notations sur les opérations militaires, à des rencontres avec écrivains et intellectuels, à l’examen de soi, des hommes et de la nature, aux amours, aux rêves, aux lectures. Jünger lit notamment la Bible; le christianisme devient pour lui un allié contre le nihilisme triomphant. Sans dissimuler son hostilité aux nazis et à l’antisémitisme officiel (il lui arrive de saluer militairement les porteurs de l’étoile jaune), il reste à son poste et n’attaque pas le régime de front. On parle d’émigration intérieure pour qualifier cette position complexe, que les contempteurs habituels de Jünger simplifient à l’envi. Hannah Arendt était plus nuancée. Tout en constatant les limites de cette attitude, elle voyait dans les journaux de l’occupant Jünger « le témoignage le plus probant et le plus honnête de l’extrême difficulté que rencontre un individu pour conserver son intégrité et ses critères de vérité et de moralité dans un monde où vérité et moralité n’ont plus aucune expression visible ». NB. Présentations de Gallimard |

|||||||||

June 20, 2001

BOOKS OF THE TIMES

For God, Country and Pouilly-Fuissé

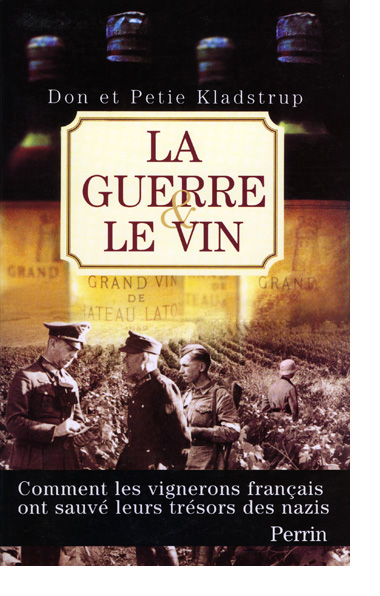

WINE AND WAR

The French, the Nazis and the Battle for France’s Greatest Treasure

By Don and Petie Kladstrup

Illustrated. 290 pages. Broadway Books. $24.

By RICHARD BERNSTEIN

The first thing to note about Don and Petie Kladstrup’s book on »the battle » (as the subtitle puts it) to control French wine during World War II is that the battle was not very complicated, certainly not compared with other aspects of the French-German struggle.

Essentially, as the Kladstrups tell it, French winemakers found various ways to hide much of their most valuable wine, for example the complete stock of 1929 to 1938 Romanée-Conti stored behind a false wall by the Burgundy wine merchant Maurice Drouhin. The Nazis requisitioned wine for themselves and their troops, sending German wine merchants, known as weinführers, to France, where they forced wine growers to sell large quantities of their product.

Vast collections of wine were found in Germany at the war’s end, including a half-million bottles of some of the best squirreled away at Hitler’s famous Eagle’s Nest retreat in Bavaria. And when the vineyards in France were struggling to recover from the devastation of war, the wine hidden a few years earlier by the French was recovered, providing some financial relief for the shattered industry.

»Wine and War » in other words provides an interesting account of one of the secondary aspects of the war that add to our understanding of the larger struggle. Its underlying theme is the Nazis’ habit of looting the treasures of the countries they occupied. And arguably France, with its wine, its Gobelins tapestries, its linens and its art, had the greatest treasures.

The story of the art, as told, for example, in »The Lost Museum, » Hector Feliciano’s deep investigation, seems a far richer one than the story of the wine, and it is a story with a far different moral flavor than the one told in »Wine and War. » The Kladstrups provide a rather heroic portrayal of French vintners, who, they say, found many ways to resist the Nazis. By contrast, at least in Mr. Feliciano’s telling of the story, many French art dealers were happy to cooperate with the Nazis in taking possession of art, especially art owned by Jews, much of which was not returned even half a century later.

The Kladstrups’ account of the battle over wine is a competent one, but it is thin, like an underaged claret. They tell some interesting stories, like the discovery of the Eagle’s Nest cache by Bernard de Nonancourt, the scion of a great Champagne family who was a member of the Free French forces who helped to liberate Bavaria at the end of the war. The authors recount the postwar trial of Louis Eschenhauer, a Bordeaux wine merchant who increased his fortune by dealing with the Nazis. But strangely, the Kladstrups (he is a former network television correspondent in Paris; she is a freelance writer) roam their subject in overly economical fashion, as if they were afraid that developing their themes more fully would have taxed the reader’s attention.

They raise subjects and then move on to something else just as things seem to be getting interesting. They tell the wartime stories of vintners from different regions of France, but few of them emerge very memorably.

Among those introduced are the members of the Miaihle family, owners of several prestige Bordeaux vineyards, who sheltered two Jewish-Italian families at Château Palmer, one of their estates. Perhaps the most interesting are Maurice Drouhin and Robert-Jean de Vogüé, the head of the Champagne house Moët & Chandon, both major figures in the French wine world who actively helped the Resistance, and went to prison.

The book makes many references to the Resistance, especially among the winemakers. »Throughout France, on both sides of the Demarcation Line, » they write at one point, »Resistance groups sprouted like weeds in the vineyard. » But the Kladstrups don’t describe much actual Resistance activity, certainly not of the armed variety, though they devote a chapter to what they call »hiding, fibbing and fobbing off, » the small ways in which the French showed their dislike of the occupier. These include gestures like putting grand cru labels on ordinary wine or providing bad service to German officers in restaurants.

The Kladstrups do write about a wine grower from the Touraine named Jean Monmousseaux, one of the founders of the Resistance group Combat. Monmousseaux created a technique of smuggling what the Kladstrups call »Resistance leaders » across the border between the occupied and the nonoccupied zones of France. But who were these Resistance leaders and what were they doing? We do not find out in this book. The Kladstrups do provide some detail on the careers of Maurice de Nonancourt and his brother Bernard.

Maurice organized a large-scale escape of men being called up for forced labor in Germany, but his plan fell through when the men in question grew faint-hearted just as the plan was to be put into operation. Maurice then decided that he had to escape, but the Gestapo »picked up his trail almost immediately and arrested him. » Reading this, one is naturally curious to know where this happened, how, under what circumstances, but the Kladstrups do not say. They provide some detail about Bernard’s escape from France to join the Free French forces in England, but here, too, the story is skimpy.

Bernard got to the home of two elderly distant cousins in the unoccupied zone, but he had lost his trousers and shoes while hiding from a German patrol in a river. His cousins provided him with a pair of their grandmother’s bloomers to wear and it was in them, the Kladstrups say, that Bernard embarked on a long trip by bicycle to Grenoble.

Did he really pedal toward Grenoble »still garbed in bloomers, » an attire that would not seem the best way for a would-be member of the Free French forces to travel incognito? The next time we meet Bernard de Nonancourt, he is in the French Second Armored Division racing the Americans to be the first to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest lair. What happened between that and the bicycle ride in bloomers sounds like a story. Unfortunately it is one not told in this book.

© THE NEW YORK TIMES June 20, 2001

Traduction française : LA GUERRE ET LE VIN, Comment les vignerons français ont sauvé leurs trésors des nazis, Editions Perrin, octobre 2004, 247 p., 19,50 €. Edition de poche octobre 2005, 8 €.

Voir aussi le documentaire Le Vin sous l’Occupation d’Albert Knechtel, diffusé sur Arte le 17 novembre 2004.